- ADHD Definition and Behavioral Effects

- The Concept of Attention Deficit

- Reasons for the Increase in ADHD

- Drug Treatment and Effectiveness

- Misconceptions in Treatment

- Scientific Debates and Differences

- The Role of Cultural Factors

Beyond “Deficit”: Understanding ADHD in a Demanding World

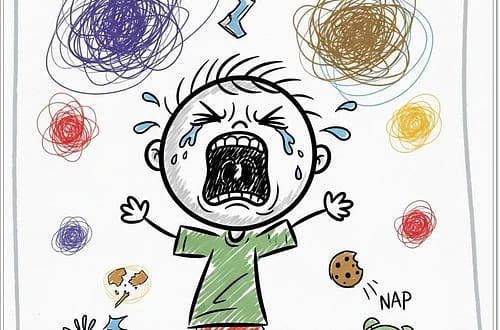

A conversation on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) often begins with its name, which can be misleading. The term “deficit” implies a permanent, intrinsic lack, akin to a vitamin deficiency. However, a more accurate conceptualization might be “attention insufficiency” – a situation where environmental demands and expectations exceed an individual’s current capacity for attention, focus, and self-control. This is not a static shortage but a dynamic mismatch, particularly evident in challenging environments.

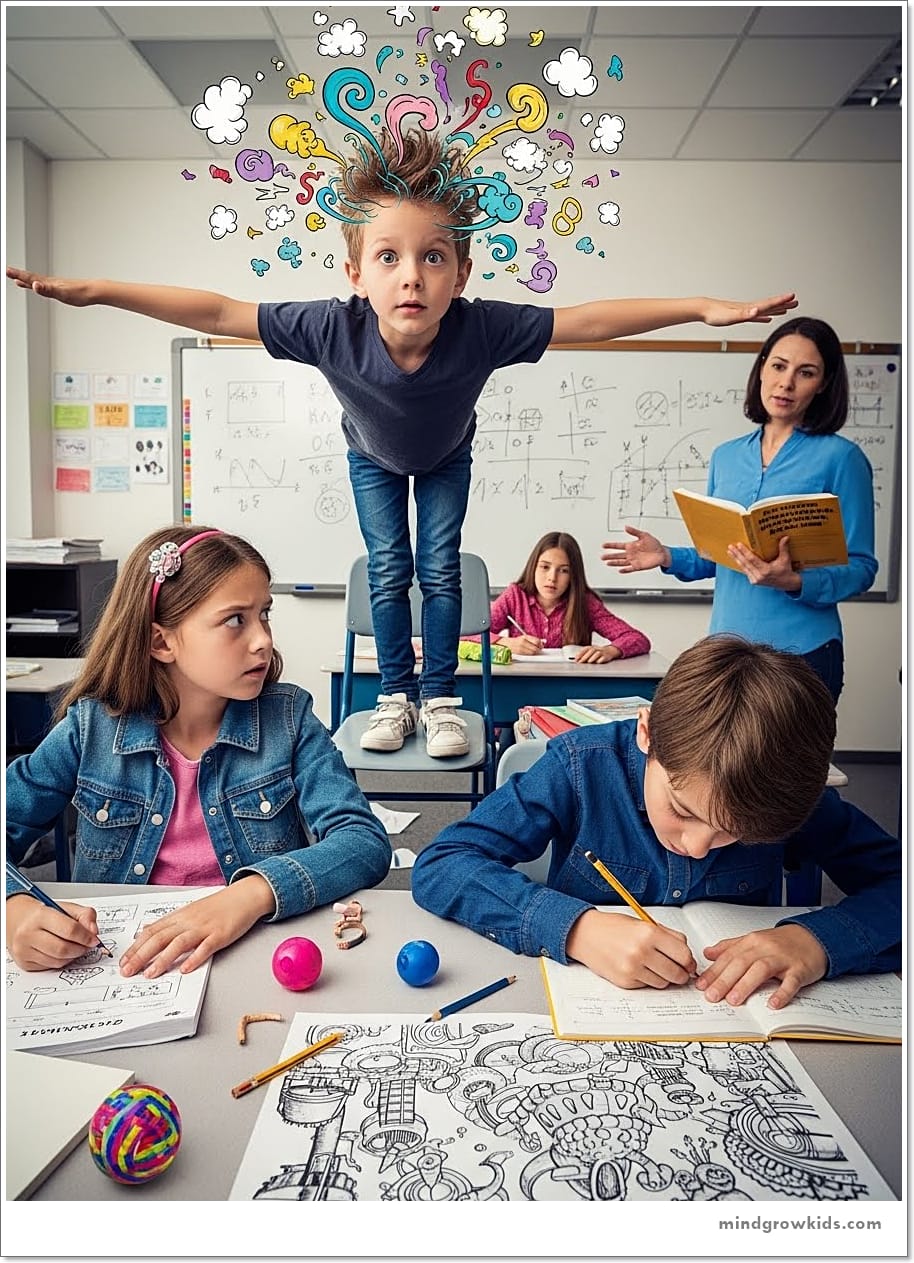

The Crucible of the Classroom

Nowhere is this mismatch more apparent than in the school environment, which can be a demanding, even “wild” arena. It is a place of competition, achievement, learning to collaborate, and navigating complex social dynamics. It requires intense focus and self-regulatory functions. When a child’s capacity for these functions is developmentally out of sync with these demands, the “insufficiency” becomes apparent, leading to the characteristic symptoms.

It is crucial to understand that ADHD is not merely about being fidgety or distractible. It is a behavioral syndrome rooted in a developmental irregularity of the brain’s attention and executive control systems. The core issue is often a delay in the development of self-control mechanisms. This delay can cause individuals to miss or delay crucial developmental opportunities, especially in the first 15-20 years of life, affecting their psychological and social standing. Consequently, ADHD can lead to various complications, including a higher risk of accidents, susceptibility to addictive behaviors, and emotional challenges.

Diagnosis: More Than Just Symptoms

Diagnosis goes beyond observing common behaviors like daydreaming or restlessness, which everyone experiences occasionally. The key is “functional impairment” – the symptoms must significantly interfere with the individual’s life, preventing them from functioning as expected compared to their peers. This impairment can manifest academically, socially, or emotionally, often leading to feelings of inadequacy and a fractured sense of self, especially in children and adolescents forming their identity.

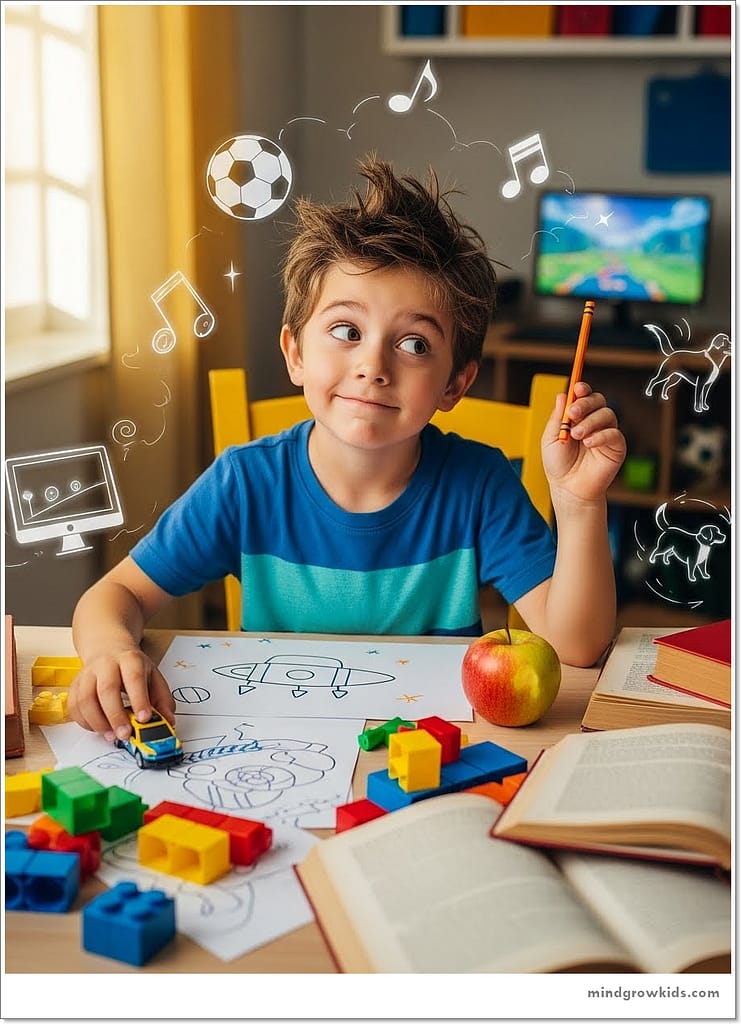

The presentation can be inconsistent. A child might focus intensely on a video game but struggle to pay attention in class. This is akin to a car performing well on a showroom floor but struggling on a mountain road; the school environment is the challenging test drive. Furthermore, symptoms may not appear uniformly across settings, sometimes being prominent at school but not at home, or vice versa.

High Cost and Compensation

Many capable individuals, including those with high IQs, develop ADHD. In such cases, core behavioral problems might not be the primary presentation. Instead, the immense effort required to compensate for attention difficulties can lead to mental exhaustion, manifesting as emotional symptoms like anxiety, depression, or social friction. These individuals often achieve success but at a high emotional cost—through extreme effort, sacrificing social opportunities, and experiencing chronic stress. This “masking” is particularly common among girls and women, which may partly explain why ADHD was historically underdiagnosed in females.

The Role of Environment and the “Boom” in Diagnosis

The notable increase in ADHD diagnoses stems from multiple factors: greater awareness, better diagnostic access, and expanded treatment options (including educational accommodations). However, broader societal changes likely play a significant role. We live in an increasingly complex, fast-paced world that often incentivizes instant gratification over patience and self-control. Environments that do not encourage these functions can lead more people to exhibit ADHD-like symptoms.

Environmental factors are powerful modifiers. Studies show that larger class sizes and early school enrollment (e.g., starting at 60 months instead of 72 months) are associated with higher rates of ADHD symptoms. This suggests that placing developmentally inappropriate demands on children can elicit or exacerbate these behaviors. Designing supportive environments—like smaller classes or flexible learning structures—benefits all children, just as creating wheelchair-accessible spaces benefits everyone.

Rethinking Long-Term Treatment

Recent long-term studies, like the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA), offer nuanced insights into treatment. They indicate that while medication is highly effective, especially in the initial years, its benefits may not be sustained at the same level over many years for everyone. This doesn’t invalidate medication but highlights the importance of using the stability it provides initially to build lasting skills through therapy, parental training, and educational support.

The course of ADHD is often variable or “wavy.” Many individuals do not require lifelong medication. They may use it during critical periods (e.g., during education) and later manage well with psychological strategies, organizational skills, and supportive environments. A smaller percentage may have a more persistent and severe course. Factors like co-existing emotional dysregulation, anger issues, or a history of negative experiences can predict a more challenging trajectory.

Conclusion: A Condition, Not Just a Disease

ADHD is best understood not as a fixed disease but as a condition—a neurodevelopmental variation that makes navigating standard expectations particularly challenging. When this condition significantly disrupts life’s natural flow and leads to complications, intervention is beneficial. The goal of intervention—whether pharmacological, psychological, or environmental—is to help individuals claim their right to a fulfilling life from their experiences.

Ultimately, the rise in ADHD challenges us to reflect on our societal structures: What has changed in our collective lives that makes focus, patience, and sustained effort increasingly difficult for so many? Addressing this question is as important as treating the individual.